|

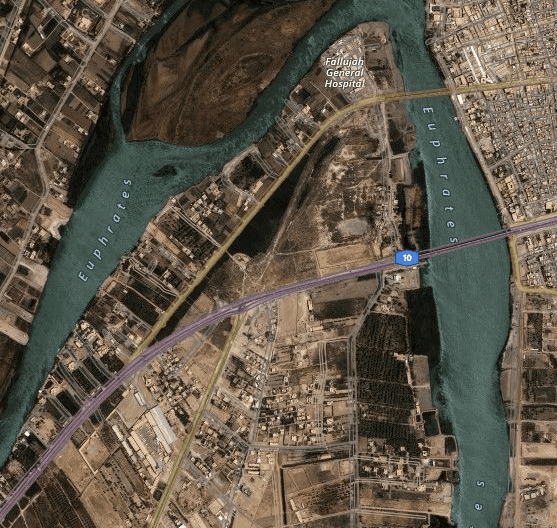

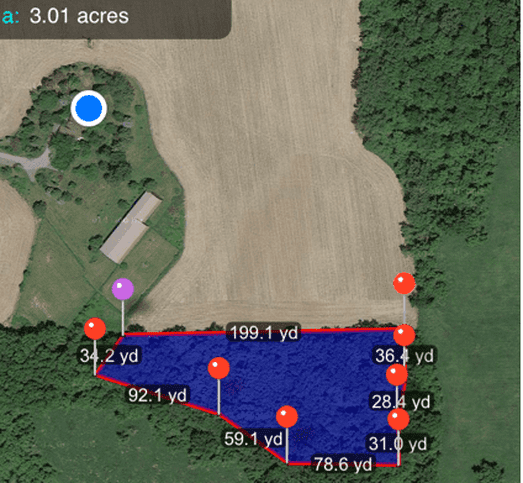

I’m still catching up from last year. I have electric fence I need to pull because I hadn’t built a hand-crank roller for steel fence wire yet when the sudden weather shift froze my posts in the ground. I have a little bit of corn left to hand pick. I need to organize my workspaces so I spend less time getting to tools. I still have pork to sell. But I can’t let the backlog of overdue to-do’s impede planning for the coming season. Within ninety days, I need to have my next field and pasture layouts finalized, have cover crop seeds on hand —if not already sown, and have the first batch of pigs ordered and on their way. Like warfighting, I can’t let myself get so bogged down in the immediate targets that I lose sight of the bigger picture. I do a lot of my planning while staring at a farm map. Spreadsheets and lists galore cover my virtual desktop and desk, but data can be slippery to recall when I walk the ground; images stick with me. As a Marine infantry officer, I lived by maps—spent hours pouring over satellite imagery to plan operations. The more time I spent at the map, the easier it was to adapt to changing situations once we were on the ground. Even when we worked the same area for a few months, I’d still stare at the giant wall map in our Combat Operations Center, visualizing my platoons’ patrol bases, looking at patterns of enemy activity, trying to see what we had missed, developing the next plan, wondering how to do this better. Ten years later and a third of the globe’s spin away, I realize that the way I thought about fighting influences the way I think about farming. In the military, we talk about “setting conditions” with operations that facilitate achieving the larger mission. A focus on setting conditions defined my company’s experience in Iraq. Our constant patrols denied the insurgents the freedom to operate (crooks don’t rob the gas station when the cops are there), but that security would have been short lived (like weeding) had we not been focused on larger, longer-term goals. Our patrolling style emphasized Marines’ daily interactions with the locals—getting to know them and treating them with respect— which set the conditions for Iraqis to begin trusting us. That budding trust allowed us to begin working with the tribal sheiks. Instead of controlling everything ourselves, we worked through the sheiks (empowerment), providing funding, training, and weapons to their local security forces (picked by them, vetted by us). That set the conditions for Iraqis to take responsibility for their own security and root out insurgents by combining their local knowledge with our military support. It worked far better than we had even hoped. (I’m strictly speaking about 3rd Battalion, 6th Marines’ deployment from January to August of 2007 in the rural villages between Fallujah and Ramadi.) My role in all of this was setting an attitude and outlook for the company, pushing decision-making to the squad level, and being on the ground as much as possible, observing, learning, and tying events to the bigger picture while often staying out of the way to let Marines do their jobs. What’s that have to do with farming? I’m not some all-knowing overseer and builder who takes raw materials from plant and animal and hands you a finished product. I’m a facilitator, a student trying to work in partnership with nature. I raise pigs, but the pigs do the growing themselves. I set the best conditions for the pigs to grow well by letting them live truest to their nature— grazing, rooting, playing, and eating in the lowest stress, most humane environment I can create. I build soil, but it’s the microbes that do the work. I plant cover crops and look for the best ways to manage those crops and the animals on them to support the microbial life. I manage the woods, but it’s the oaks and hickories that provide the food, shade, and shelter to livestock and wildlife, that filter our air, and provide lumber and firewood at the end of their life cycle. I try to set the conditions for the trees to do their job better by thinning crowded stands and propagating new ones so the trees will be healthier, more productive, and last well beyond my lifetime. I bring bring a certain outlook, provide the labor, and keep looking for better ways to let nature do its job. Plan, set things in motion, and sometimes get out of the way and observe. I look over the top of my screen and out the window at harvested corn and snow-covered pasture. Then I look down at the farm map, developing the next plan, wondering how to do this better.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Ryan Erisman

Former Marine Infantry Officer. Iraq Vet. Interested in Regenerative Agriculture at any scale. Archives

February 2023

Categories |

Odyssey Farm, LLC.

The Odyssey Farm Journal

Odyssey Farm, LLC

|

Dane County Climate Champion

|

608.616.9786

|

Copyright © 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed