|

“Do you think you could teach a class that relates The Odyssey to the modern veteran’s experience?” Our friend Evelyn, a high school English teacher, asked me three years ago.

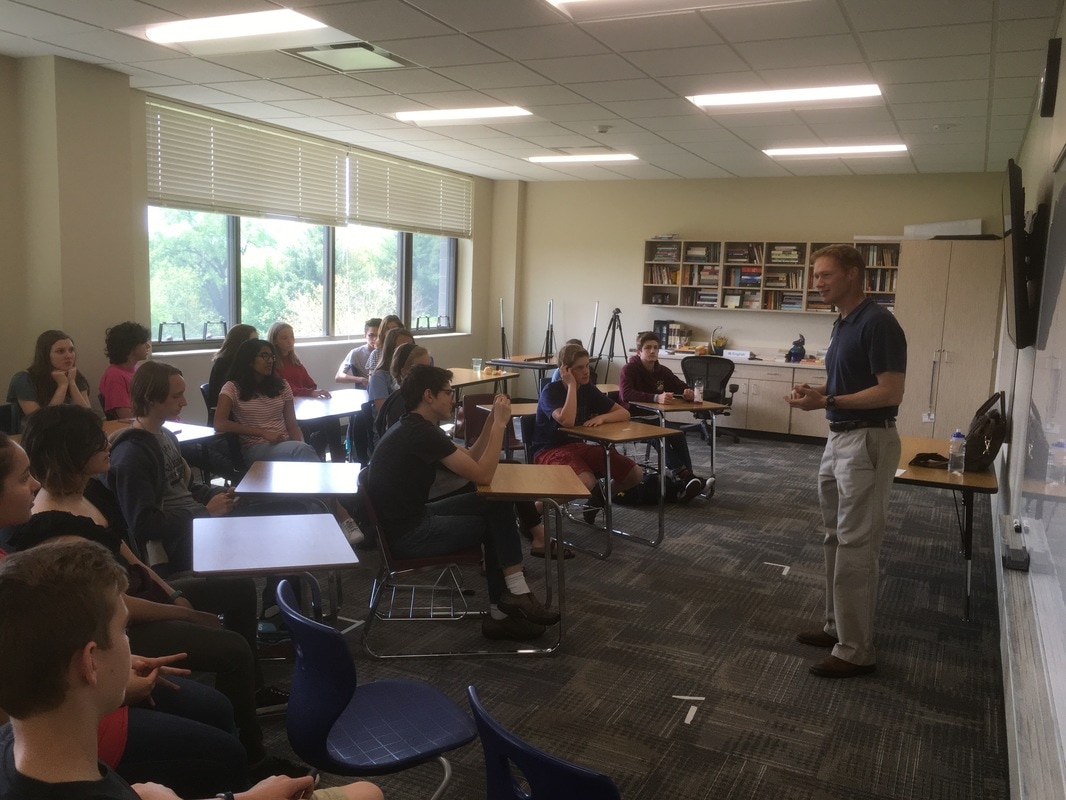

“Sure,” I said. I re-read The Odyssey and realized that I didn’t identify at all with Odysseus. He doesn’t seem motivated enough to get home, he doesn’t delegate anything or trust anyone, and he eventually gets all of his men killed. Still, several aspects of his journey still resonated with me, and I discussed the parallels I found with Evelyn’s English class in May 2014. It must have been ok, because I taught the class again last week. Between teaching those two classes, I started Odyssey Farm, which has given me another perspective on the journey. I’ll spare you the class outline for now because the most interesting learning point—for the students and for me— came from the students’ questions: “How did you work through your struggles after returning home from the war?” First of all, the assumptions behind these kinds of questions annoy me. Several times over the years that I did presentations for the Farmer Veteran Coalition, I had strangers who didn’t know my military background tell me, “you need to heal,” or something to that effect. They meant well, but the general assumption I hear in that statement is: Veteran = Broken. “I didn’t have any PTSD or nightmares,” I explained. I stayed in touch with fellow Marines up and down the chain of command. I made new civilian friends when we moved back to Seattle. I got into woodworking and ultra-running. Sarah and I biked, backpacked, and kayaked throughout the Pacific Northwest. I came home to a great network of family and friends. I was happy as hell to be starting a new chapter in my life. “So what do you mean by ‘struggles’?” I asked the class. One young man in the front row clarified their question: “Did you have trouble making the psychological transition from combat back to civilian life? I explained that after leading a rifle company in Iraq, nothing I did felt as challenging, interesting, and important enough to throw myself into as a vocation. My ultra-running was a great challenge but it only served me. Woodworking served me and a few others at best. I started thinking out loud. “The real struggle was that I had to find new struggles.” Now they were drawn in. Or maybe I just confused them with the mental hairball that I’d coughed up. “I mean, I need to struggle,” I said. I explained to the students that Odyssey Farm is thirty-two acres and that I do most of my work with a walk-behind tractor or by hand —such as hand-picking corn. (Another teacher, whose husband had deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan with the National Guard, laughed out loud, “Oh, you are a Marine.” Compliment taken.) After combat’s life and death decisions and counterinsurgency’s complexity, nothing else has satisfied my need for combined physical and intellectual challenge and a sense of purpose as raising food in partnership with nature to feed my family and my community. I enjoy the challenge and the process of farming this way. My answer about taking on farming as my new struggle inadvertently reinforced some of the parallels I’d already drawn to The Odyssey: —Transition is harder than it first appears: Odysseus’ ships are within sight of Ithaca when his men open the bag of winds which blows them all the way back to Aeolia. I integrated very easily back into civilian life but struggled to find a calling that felt equal to my challenges and rewards of leading Marines. And I’m just beginning to go down this new path. —The need for a mission: Odysseus turns several events of his return trip into battles. I don’t go around picking fights, but I do understand the desire to take on a “mission” —some larger purpose that engages me fully. —Arrival is a temporary state: Odysseus finally makes it home only to leave again. Every time I accomplish something that I’ve been working toward, it becomes a stepping-stone to the next thing I need to learn or want to do. “I think we all need to struggle in our pursuits,” I told the class. I’ve since learned that my gut response about struggle is backed up by the work of psychologist Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi. According to Csikszentmihalyi, we achieve our greatest satisfaction when we engage in something that perfectly matches a high level of challenge to our own high skill levels. He called that perfect match of challenge and skill Flow, what we often think of as being “in the zone”. Selected struggle isn’t just for wacky-former-Marine-infantry-officers-turned-horseless-Amish-farmers (or the ancient Greeks). We find our best selves in that sweet spot where bringing all of our knowledge and skills is just enough to meet the challenge.

0 Comments

The best cornbread I’ve made begins a few steps prior to most recipes. I start by shelling corn.* I’ve grown Hickory King, Reids Yellow Dent, and a few others in my quest for good cornmeal (and when it’s not the best cornmeal, it’s still great hog feed). Gene Logsdon wrote that some people found their favorite cornmeal came from popcorn. I only grow open-pollinated corn, old varieties from which you can save the seed and replant (if you plant hybrids, you have to buy seed every year from seed companies).

Since I can’t get much separation on 15 tillable acres, I had some cross pollination between our Pennsylvania Dutch Popcorn and our Reids Yellow Dent corn. The kernels are popcorn-shaped, a mix of white and yellow throughout the ear. It doesn't pop well, so I shelled and ground some yesterday and made cornbread. It's excellent. The cornmeal has a much stronger flavor and aroma than most cornmeal I’ve tried. I often fall down the rabbit-hole of small-scale, labor-intense production, but the discoveries are worth it at times—the eating down here is wonderful. I use a King Arthur Flour recipe for cornbread. I’ll have some cornmeal for sale at the Madison chapter’s Weston A Price Foundation meeting tomorrow night in Monona. Details Here. --Video of the hand-cranked sheller in action. *Actually, I start by building soil with cover crops before I even prepare ground for planting. That may seem like a long reach back, but the point is to raise animals and crops with the best flavor. As mentioned in the Underground Secrets of Nutrition post, flavor begins with soil. “You are what you eat eats.” In six words, Michael Pollan nailed a profound truth about health and nutrition. We eat plants. We eat meat from animals that eat plants. Healthy plants are key to our own health. What makes for a healthy plant? In, The Third Plate, Dan Brown explains how the best tasting and the healthiest food comes from the richest, biologically dynamic soil. Here’s my quick takeaway from Part I, Soil:

In 1942, a time when people’s food still came from close to home, Dr. William Albrecht, a scientist at the University of Missouri, studied the state's military draft rejection rates. Albrecht created a map of recruit rejections for ill health. The highest rejection rates came from the state’s diluted soils of the southeast while the mineral-rich soils of northwest Missouri produced much healthier men. Albrecht understood that soil microbes “dined at the first table,” and that soil lacking minerals could not grow healthy plants. He warned that the nation’s declining soil fertility would lead to a health crisis. Fast forward sixty years. Not long after chef/author Dan Brown sets up Blue Hill at Stone Barns, a restaurant connected to its own farm, his farm manager tests the Brix of two carrots. Brix measures the percentage of sugar in plant matter. One carrot comes from rich soil that had been a dairy pasture for decades. The other carrot is from an organic farm in Mexico. While the sugar percentage, not surprisingly, correlates to taste, it also indicates mineralization in the soil and the biological activity to make those minerals available to plants. The carrot from the former dairy pasture measured 16.9 Brix, meaning 16.9% sugar, an amazingly high number. Brown explains that a good, sweet carrot might have a Brix of 12. He describes the 16.9 carrot as “astonishingly delicious.” The organic carrot from Mexico? Zero, as in a reading of 0.0 Brix. It’s organic, but in the industrial sense—raised in a monoculture where the farmers are adding inputs (though organic ones) instead of building the soil. Several studies over the years point to the same loss in vegetable nutrition that Albrecht predicted and that Dan Brown’s farm manager measured between carrots. Albrecht noticed in the 1930’s that cattle could get a balanced diet by grazing pastures grown on well-mineralized soils. However, when cattle were confined to a barn and fed grain, their bodies tried to compensate for the lack of micronutrients by overeating. They got fat, but not necessarily healthy. John Ikerd, a professor emeritus also from the University of Missouri, connects Albrecht’s findings to the contemporary American diet based on cheap, processed grains, and the obesity epidemic: “The lack of a few essential nutrients in our diets might leave us feeling hungry even though we have consumed far more calories than is consistent with good health.” So what can you do? Buy local vegetables when you can. (I know, this is Wisconsin, that’s not easy for much of the year). Buy them from a farmer you trust. Our mouths may tell us as much about our food as any laboratory test. Really tasty, fresh vegetables are likely to be more nutritious. What’s this mean for me? I need to stay focused on building soil fertility with diverse cover crops and less tillage that destroys soil life. I need to grow even more of my own feed for the pigs. Healthy soil=healthy pastures and crops=healthy pigs. Soil building is my obligation to the land, to the animals on the land, and to you, the consumer. |

Ryan Erisman

Former Marine Infantry Officer. Iraq Vet. Interested in Regenerative Agriculture at any scale. Archives

February 2023

Categories |

Odyssey Farm, LLC.

The Odyssey Farm Journal

Odyssey Farm, LLC

|

Dane County Climate Champion

|

608.616.9786

|

Copyright © 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed