|

Despite the pouring rain yesterday, we received a little bit of sunshine at the farm—at least metaphorically. We received our retail license.

Now you can purchase sustainably raised, low-carbon hoof-print pastured pork right here at Odyssey Farm. Retail Price List

0 Comments

You asked. We acted.

We will be able to sell Odyssey Farm Pastured Pork directly to you, by the cut, after Thanksgiving. You no longer have to own a deep freezer and buy half a hog in order to eat high quality pork from hogs that lived true to their nature—free to roam and root in pastures and the woods—raised in ways that are good for the land, good for the animals, and good for the eater. We'll still sell whole and half hogs, but you will soon be able to come directly to Odyssey Farm and buy: —Hams for the holidays —The best bacon for breakfast —Roasts for remarkable dinners —Hocks for heart-warming winter dishes —Braunschweiger (the spreadable pork-liver-candy) for anytime. Though we’ll sell individual cuts, we also offer a 25 lb variety box. The exact weight of included cuts will vary, and we can customize the cut list somewhat (there is only so much bacon on a hog), but an average box will contain: 5 lbs Smoked Ham 5 lbs Bone-in Pork Chops 5 lbs Bone-in Shoulder Roast 4 lbs Smoked Bacon 2 lbs each Breakfast Links, Bratwurst, and Ground Pork 25lb box will cost $205, much less than you would pay for the same breakdown of high quality, pastured pork cuts from local retailers. Call or email to order your 25 lb box. Boxes will be available by mid-December. Of course, you can still order whole and half hogs for the December 1st butcher date. Turn old Jack-O-Lanterns into bacon (and have some fun doing it) Jack, you're just not cutting it as a Jack-O-Lantern any more. It's time to send you out-- —to the hogs. Sorry, Jack, but this is the best outcome for all of us.

Loading hogs yesterday went better than I’d expected. I’d measured them the day before to get weight estimates. They’ve been handled and scratched enough that they don’t mind having a thin tape measure wrapped around them or across their backs. I marked the eight biggest ones with a paint stick so I could sort them quickly in the corral.

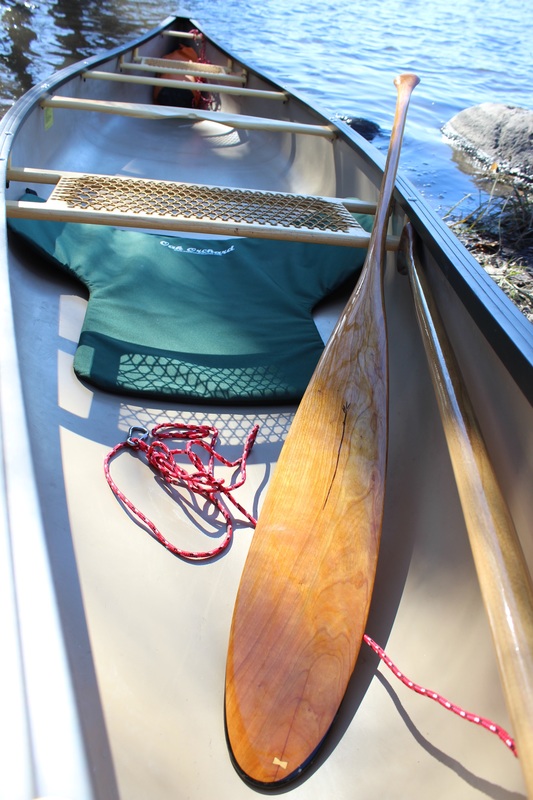

Once they were in the corral yesterday morning, the eight largest hogs were the first ones to enter the chute each time I opened the gate (self-selecting—they were probably the first ones to the feeder). In the loading area, two Berks hesitated to walk up the trailer ramp, but I still spent only five minutes coxing them in. When we arrived at Country Meat Cutters, they sat in the trailer, totally relaxed while I went inside to do paperwork. When I dropped the ramp, all but one followed me into their the holding pen. Calling them to me felt misleading, but it was also an important final step in my “good for the animal—good for the eater” philosophy. Good for the animals because they were humanely handled by a familiar face until the end. Good for the eater because their low stress should show in the meat quality. Then I went canoeing. After an entire summer and an early fall full of rain and gray days, we’ve had a great stretch of relatively warm, sunny weather. I’ve spent all of those sunny days working outside, trying to catch up. For the past three falls, I’ve planned on doing some fall paddling but never seem to get to it. Since one of Wisconsin’s many Mud Lakes sits only a mile from Country Meat Cutters, I tacked on a little mid-day me-time to my hog hauling trip. After swapping Carhartts for wool (dress to get wet—even though it’s unlikely), I pushed off from the bank and spent an hour slipping along Cottonwood-lined banks and reed islands, relishing the gentle glide and efficiency of a traditionally shaped paddle. I went back to work an hour later, but the satisfaction of a good last trip for the hogs, topped off with a nice paddle, stayed with me for the rest of the day. One question started really nagging me in mid-September:

“How does one guy sort the eight biggest hogs out of the herd to get them on the trailer?” I can move the hogs from pasture to pasture well enough. They come running when I call them and they’ll follow me. I even started preparing them for loading by parking my trailer in the pasture a couple times and putting ear corn in it; they link exploring the trailer with a reward. The good thing about a herd mentality is that everyone wants to do the same thing. The drawback to the herd’s social structure is that the hogs don’t like to be separated from the group. Getting individuals to do different things—you on the trailer, you stay here—isn’t so easy. Linebackers: When they were small, I could put them in a makeshift pen and catch individual animals to separate them. Grown hogs weigh as much as a linebacker, have a lower center of gravity, and twice the traction. I can’t physically compete against that. I didn’t grow up on a hog farm, but I grew up around them. Every time I can remember my cousins or friends sorting hogs, there were multiple people involved. I needed to build a handling system that would allow me to sort hogs alone. Temple Grandin: Animals are easier to handle when you can guide them down obvious paths. My grandfather surrounded the barns he built with fence aisles and myriad gates so he could work cattle easily in any direction. Running animals up into a corner or sorting them in a big lot where they can run back and forth to avoid being cut out of the group stresses them and the handler in a downward spiral. Temple Grandin’s studies of livestock behavior led her to develop livestock handling systems that accounted for animal’s sight, hearing, and sensitivity to movement or potential danger. Based on her recommendations, I needed a setup with narrow aisles that blocked vision to the sides and dividing gates that I could control without getting in front of the hogs. Coming back from Madison one afternoon, I whipped through the three traffic circles at the “N” exit off 94. Traffic circles. I needed a traffic circle for hogs. I love designs that are well thought out and well built, the kind of engineering that lasts for generations. I spent an hour at my desk, sketching an evolving layout for a great solid-panel handling corral. Then I slapped myself for burning an hour. I don’t have the time, equipment, or funds set aside to build a solid fence corral with heavy duty gates and all that. I needed to shift my thinking. Infantry Officer’s Course introduced me to “The 70% Solution”. In war, you don’t need a perfect plan, you need a good enough plan that works right now. I needed something I could build quickly, cheaply, and that would be just strong enough to last for two loadings. Then I could take it down and build something better later. Sanford & Son: I got a trailer load of free pallets from a wholesale materials company. The pallets are decked on both sides, so they block view almost as well as solid panels per Temple Grandin’s recommendations. I stood rows of pallets up against the fence and each other like building a giant card house. Once I established the layout, I started screwing them together with deck and lag bolts. Salvaged T-posts driven inside every third pallet braced the walls well enough. I made a sliding gate with the rollers of a horse stall door mortised into the bottom of a pallet. The rest of the gates swing on hinges or pivot on a single bolt in the bottom. Aside from two pounds of deck screws and two sets of gate hinges and straps from Farm & Fleet, I salvaged everything else. I’ll be able to recover and reuse all of it when I deconstruct the corral. Rehearsals: I wanted to test my corral as soon as I finished it on Friday. I got the hogs into the first pen easily enough, but they balked at entering the aisle. After five minutes coaxing one animal through, I opened all the gates a let them explore on their own. Once they’d been through the aisles several times and found the ear corn on the trailer, I moved them all back to the first pen, closed all the gates and started running them through one at a time. This time, they each entered willingly and waited for the next gate to open, and went where I wanted them to go. The design is far from perfect, but it works. When I load hogs on Thursday, it should be a familiar process to the hogs that results in low stress animals heading to Country Meat Cutters. When a tree falls, what do you do with it? Until our most recent generations, those who lived on the land knew the best uses for their harvested and windfall trees—from timber framing and furniture from oaks to weaving baskets and chair seats with hickory bark and willow branches. Those examples might seem like an anachronism today, but maybe they shouldn’t be. At least the thought process behind them shouldn’t be. I try to use natural resources to their highest purpose. The best most of us do with downed trees is cutting them for firewood and composting the remainder. That’s not bad. Under the right conditions, firewood is a renewable heat source. Sustainable forestry practices also recommend leaving at least twenty-five percent of any tree on site to decompose and feed the insects, fungi, and microbes that feed the soil. Depending on the tree, we can do better. The Bur Oak that fell across my fence path this the summer will be mostly firewood, but I saved three logs, waxing the ends and rolling them onto slats to dry slowly in the shade until I can get to them later, i.e., when the hogs are dead. I check my fence through the woods twice a day to make sure no branches have fallen across the wire, which could a) ground out the wire, and/ or b) create a breach for the hogs to get out. Last week, I came across a Black Cherry limb almost on the fence. Limbs usually just get tossed in a pile to decompose, but when I noticed a gentle crook without any branches extending from it, I sawed out the piece. (What? You don’t carry a folding saw in the right tool pocket of your Carhartts?) Back at the barn, split the section into two pieces with a froe and cleaned the bark off the sides with a hatchet, revealing the grain. A couple cuts with the saw defined the handle from the bowl, then I started cleaving away with the hatchet. Wood this green, i.e. wet, peels away in gratifying strips instead of chips. I had a rough shape in five minutes. I spent a few evenings working on the spoon, maybe a half-hour at at time. I even worked on it in a few five-minute sessions after lunch. It might seem odd that one project could reinvigorate me before working on another, but the spoon pointed my focus at the intersection of honed steel and grain—discover, explore, discover more. Part of working with wood like this is “reading” the grain. Every cut felt like turning the pages of a book, getting deeper into a story. The curve from handle to bowl follows the grain. The spoon remains very strong with minimal bulk that way. It also means that nature dictated the best form—I just needed to peel back layers to discover it. It’s more than a serving spoon: It’s the spoon from a Black Cherry branch I found one fall day while checking fence; the spoon I hewed out with the metal hammer-handled hatchet I begged my parents to let me buy from Orange’s Hardware store when I was ten; the first spoon I’ve carved where the final form matched the image held in my head from the moment I sawed the branch. It’s the most satisfying and simplest project I’ve done in a long time. |

Ryan Erisman

Former Marine Infantry Officer. Iraq Vet. Interested in Regenerative Agriculture at any scale. Archives

February 2023

Categories |

Odyssey Farm, LLC.

The Odyssey Farm Journal

Odyssey Farm, LLC

|

Dane County Climate Champion

|

608.616.9786

|

Copyright © 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed