|

Once they have access to the woods, the hogs spend most of their time there. They rarely use their shelter, preferring instead to make a nest protected from the wind and sleep in a pile.

They explore their environment more, snuffling along with their snouts below the leaf litter, rooting for acorns. They roll rotten logs, chew on sticks, and excavate nests. I love seeing them living as true to their nature as I can let them be. I'm enjoying it now and there's still the delayed gratification to come —bacon. See our Facebook page for a video of them rooting for acorns.

0 Comments

I have a thing for organizing my tools. Maybe it comes from those years of wearing a flak jacket and knowing by feel exactly where everything was that I needed. I won't even disagree if you say it's OCD. I'll just argue that it stands for Organized, Customized, and Designed.

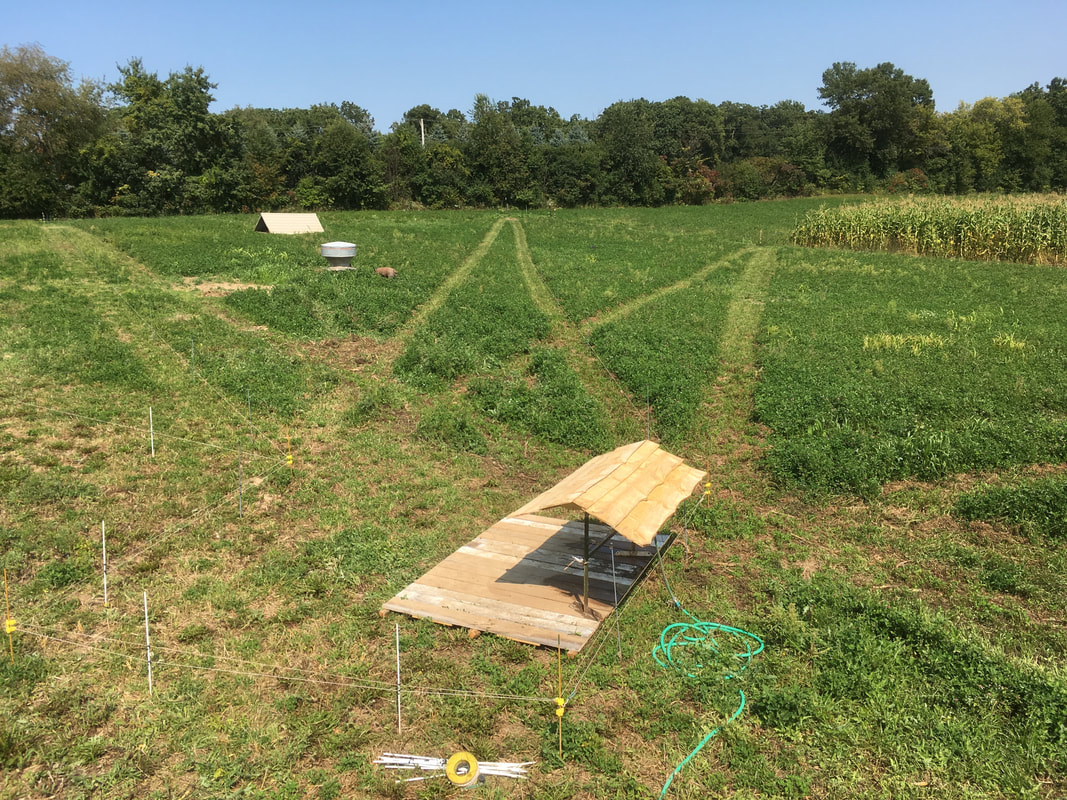

After a few trips to the woods last year to clear fence lines and fell invasives, I got tired of needing one more thing that I didn't bring. So I came up with the Saw Pack. Companies make saw packs for western firefighters and loggers, but their packs are expensive and carry the saw in a comfortable but unhandy position with the powerhead down. I wanted something inexpensive, easy to make, and allowed me to work from the upright pack like a toolbox. Stealing an idea from a friend who uses a similar rig to carry elk meat out of the mountains, I based my design around a $25 pack frame I found on Craigslist. My pack carries the saw with its 18" bar slid down in a scabbard. I store a spare bar -up to 25"— in a parallel scabbard. Another scabbard carries an axe and modified prybar/felling bar/cant hook. A one gallon gas can sits on a shelf below the saw, held in place with a bungee cord. Everything else —1 qt of bar oil, sharpening gear, spare chains, folding saw, spare scrench, water bottle, etc.— rides in a pair 1-gallon olive oil cans with the tops cut out. Half-inch conduit clamps attach all the brackets and scabbards to the frame. It's not the easiest pack to carry. Its 58 lbs rides high due to the design. But I don't have to carry it more than 600 yards, so I can manage. Wearing my safety gear —steel toe boots, saw chaps, and helmet—I can strap on the pack and have everything I need for several hours of chainsawing. I prop the pack against a tree and go to work, sliding gear and tools in and out of cans and scabbards as needed. It's OCD —just for me. Call it a wagon wheel, spoke-and-wheel, or a pie. It’s a system of grazing a pasture by moving the animals around a fixed center point. After trying this system with cattle a few years ago, I adapted it to pigs. I call it the pig-star.

Without a tractor on the farm, I needed a pasturing system that let me move pigs easily. Otherwise, if I left them in place too long, they would tear up a pasture beyond easy repair. When you only have pitchforks, shovels, and a tiller, pasture renovation isn’t easy. Pigs need water, shelter, and feed. The hardest thing for me to move is the watering system, so I built the pig-star with my watering system—what I call the water-deck—in the center. I fenced in eight acres of pasture this year with two-strand steel electric fence. I don’t need that much fenced in but it’s easier to build big and not need it than to have to fence in more pasture in mid season (Experience, thou art a tough teacher). I lay out one to three-acre paddocks depending on the pasture constraints and the size of the pigs —larger animals need more space. A mapping app on my phone helps me find the center of the paddock and get the most even divisions. Then I make a fifteen by fifteen foot box in the middle of the paddock for the water deck and set steel electric fence posts at the box corners. I mow lines from every dividing point on the outside perimeter to two of the posts around the water deck; some of the divisions require me to change the fence opening to the water deck and some do not. The resulting layout looks like star (see photo above). I divide the paddocks with single strand of poly wire (synthetic twine with stainless wire in the strands —lightweight but still carries a shock) and fiberglass posts. I use separate wires for each leg of the star and and always have the next leg set up as well. When I need to move pigs, I unplug the fence, unroll the wire between the old and new divisions, move the feeder and shelter, and put the wire back up. Then I take the outside wire of the previous division and set it up for the next new division. I can move pigs in less than ten minutes this way. It takes a couple minutes longer if I change which side of square is open to the water deck or rotate the water deck itself. I’ve been told several times that once pigs are trained to electric wire, they won’t cross where a wire has been. A lot of farmers recommend putting up hog panels where you change paddocks so the pigs will cross easily when you take down the pannel. I used to do that and decided it was too much labor. Though they were hesitant the first few times I moved them, my pigs quickly learned to cross into new pasture as soon as I rolled up the dividing wire. I also feed them ear corn (and now acorns) from a bucket every day. They run to the sound of me banging on a plastic bucket. I fill the feeder every other day and time it so that it’s empty when I need to move them. Then I tilt the feeder on its side and roll it to the new division. I put old cultivator gauge wheels on one end of their shelter so I can pick up one end and move it more easily. Both have tow hooks on skids underneath so I can drag them with my BCS for longer moves. I’ve had people tell me that I need a four wheeler or UTV for all of this. I’ve watched farmers get off and on a machine to open and close gates, off and on to cross wires, off and on to fill the feeder, etc. At this scale, I can carry two bags of feed straight from barn to feeder and step over fences faster than I could do it with any machine. If you go through a ton of feed per week though, that’s a different situation. That’s the pig star. They are in their third “star” for the summer. I only use the BCS when I move them to a new star, about once a month. So I can go a month at a time without firing up an engine to move or feed pigs. When you look at the labor/overhead/environmental factors equation, it’s not a bad way to rotate pigs through pasture. A customer who dropped by the farm for the “nickel tour” saw my tool tote and thought it was wonderful that I was using “that old toolbox”. I used to think that carpenter’s totes like the one above were quaint relics best used as planters and country decor. Then, a couple years ago, I made one as one-hour hand tool project using barn wood from our farm in Watertown.

I can get 50 lbs of tools in a Bucket Boss, but it’s not handy to carry. The classic tote, with a tool racks along the inside, lets me carry plenty of tools more comfortably than a bucket. The narrow cross-section puts the weight closer to my body, making it feel lighter. Though lidded tool boxes with drawers keep dirt out, and they’re great for mechanic’s tools, they’re much slower to access. For taking a few tools to the task, the tote rocks. Everything stands up in a tote so it’s easy to grab a tool, use it, and put it back in it’s slot. I use this tote for chainsaw gear when I’m milling logs, for carrying axe, maul, and wedges when I’m splitting wood, and for fencing tools. It’s easy to slip stuff in and out of it as seasonal tasks change. Sometimes the only way to understand why people did things a certain way is to try it. Who knew that an 19th Century styled carpenter’s tote could still be so handy? “What are you up to?” a friend asked over the phone on Sunday.

“I’m checking out Viking chicks.” “O k a a a y— Uh… is that website or something?” “No. Well, it probably is. But I’m talking about chickens. Our broody hen just hatched five Icelandic chicks.” When a hen gets broody—the instinct to sit on eggs and hatch them—we try to break the habit since broody hens don’t lay eggs. If you don’t break the broodiness in the first couple days it can last a couple weeks. When one of our Buff Orpington hens got broody, we couldn’t break her. We’d pull her from the nest box several times a day, pull the other eggs out of the box, and even put frozen water bottles under her. Nothing worked. Failing to redirect her nature, we got the chance to work with it. Friends of ours who keep flock of Icelandic chickens—a resilient, dual-purpose breed brought to Iceland by the Norse over a thousand years ago—gave us six fertilized eggs. We put the eggs under the hen we started calling Broody and waited. Three weeks later, the day I started building a nest box in the chicken tractor, the chicks started hatching. I'd never been close to a hen with chicks. We wondered if the hen would even be a good mother since she was raised in a brooder and the chicks weren’t from her eggs or even her breed. Three chicks had already hatched when I transferred her from the barn to the much safer chicken tractor. When I carried her nest box to the chicken tractor and picked her up, there were only three eggs beneath her and no chicks. Shit. Did they get out of the nest already? Did the barn cats get to them? As I lowered Broody into the chicken tractor nest box and glanced around for smug cats, three chicks dropped from beneath Broody’s feathers -peep, peep, peep. Talk about tucking them in. By evening, five of the six eggs hatched (the sixth turned out to be unfertilized). Within twenty-four hours, they were following Broody around the tractor, pecking, scratching and peeping along with her. I’m liking my Viking chicks. Wisconsin supposedly drinks more Brandy per capita than any other state. Californians drink more total, but they have seven times more people. And it's not just Brandy, it's Korbel. As of 2004, one-third of Korbel's total production went to the Badger Stage.

I didn't get the brandy thing until we started frequenting Friday night fish fry at local supper clubs and taverns. Bartenders were slinging together brandy old fashioneds by the tray full. I always thought of it as an old-guy's drink, something for people who've been going to the same supper club since the Johnson administration. Then I tried one at Quimby's Grove on the south side of Madison. I like my gin & tonics. I like my Manhattans. But at a fish fry or up north, I now drink old fashioneds. Yesterday, I decided to make bourbon-brined pork chops. Kneeling in front of the liquor cabinet, I considered my options and tried to decide what would have the best flavor. Then I spotted an almost-empty bottle of Korbel left over from a party (I don't make old fashioneds for myself at home). I poured a shot to sample the flavor and imagine it in a marinade. Brandy-Brined Pork Chops: See the recipe for Bourbon-Brined Pork Chops. I substituted Korbel for bourbon. I also used only one cup of cold water since the chops (which I hand sawed out of a frozen loin roast because we're out of chops) didn't have a lot of room to spare in the pyrex container I used. I seared them at 500 degrees on the grill and then turned it down to medium low (these were 1-inch chops) and cooked them until the meat thermometer read 140 degrees. Wow. Try a brandy-brined pork chop and you may just skip the supper club and eat at home. *Arabic: "Thank You" Yesterday, while driving down to Albany to have our chickens processed, I spotted an Amish woman leading a dairy cow and thought of Iraq. I spent most of my second tour in Iraq in rural areas between Fallujah and Ramadi. We lived in the villages, patrolled among the people every day, and glimpsed an entirely different world when we didn't have to look at it through gun sights. We treated Iraqis with respect and dignity, knowing that the majority weren't the enemy, but that the enemy hid among them. In the counter-intuitive calculus of counterinsurgency, we brought about security by making ourselves vulnerable, by getting close to people, by interacting. I would never call myself a poet, but a few years ago at a poetry slam during the MOSES Organic Farming Conference, this memory hit me all at once and I scratched out the poem just in time to read it on stage. The poem describes that same memory from Iraq that hit me again yesterday. Shukran

We patrolled through pink-petaled orchards Swept for IEDs in alfalfa fields When Marines and gun trucks escaped my view War and Time evaporated. A hedgerow fringed the Euphrates Its tangled fingers sweeping the ocean sky Like the hedgerow on our farm’s bottom pasture Across the wide, muddy creek. Squad position reports through my earpiece Crackled me to the present Following my order To not disturb livestock or gardens The squad skirted wide around a grazing dairy cow Tied to a stake in the field. The bony cow still spooked, tore at the rope, Tangled her hooves and horns And thrashed on the ground Her once-gentle brown eyes drawn wide with fright. I slung my rifle behind my shoulder and approached her side. “Easy girl, easy” Bracing her front legs with my knees, I rubbed her shoulder. “Easy girl, easy.” And untangled the rope, Her flesh twitching under my hands. A burka-clad young woman kneeled at the cow’s head. Her delicate hand brushed mine across the animal’s leg. She breathed a startled whisper through her veil, Her once-gentle brown eyes drawn wide with fright. “Shukran” At the end of an organic field day today, farmers drifted into various groups and conversations as usual. The conversation circle I joined included several Amish farmers. I was showing some other farmers how I could plant and seed with the BCS. When the Amish men leaned in to look at the phone pics around as well, they all started shaking their heads and laughing. I heard one of them say, "crazy".

"Well, you're not afraid of hard work," one of the older men said in a respectful compliment. We all had a good laugh, but when the Amish start to make fun of your technology, it might be time to re-evaluate. My combat engineer squad leader crouched next to me with two sets of wires ready to touch off to a battery. I looked at my watch and then at the sergeant.

I nodded. “Now.” My entire rifle company hunkered out of enemy view in two wadis, coiled to attack while the desert sun rose behind us. Our engineers had set explosive breaches in the two enemy minefields that blocked our paths. The whole attack would kick off with a dummy breach in one minefield, followed by 81mm mortars and artillery dropping the smoke and high explosives on three known enemy strongpoints. With the enemy thinking we were coming from one way, and unable to see our attack, the engineers would blow the second breach —the one we now crouched behind—so we could begin our assault on three enemy positions. Months of training as a company and days of planning, orders, and rehearsals all led up to this moment. An enormous “CRACK” just over the berm threw dust and gravel into the air. The shockwave smacked the entire company with a collective What-The-Fuck, but I yelled the words out loud. The sergeant had blown the wrong breach. He looked at me wide-eyed and hands shaking. A major wearing a blaze orange flak jacket and carrying a clipboard raised his eyebrows above his sunglasses. This wasn’t a real attack, it was Range 400 at Twenty-nine Palms, California, a collegiate-level exam in a rifle company’s ability to shoot, move, and communicate. The major looked at me with a wry grin, “What now, Captain Erisman?” I radioed my Fire Support Team leader and all the platoon commanders on the net, “Wrong breach. Wrong breach. Go with the same fire support plan. Start dropping smoke and H-E. The enemy still won’t know the dummy breach from the real one. Hell, they’ll be just as confused as we are.” The major smiled and jotted something on his clipboard. I looked back down at the sergeant. “No worries. No worries,” I yelled over the steady crumpf of mortars and duh-duh-duh-duh-dum of heavy machineguns. “We’re gonna roll with this.” And roll we did. Evaluators called it one of the better attacks they’d seen in a long time. In Iraq, I learned to roll with life-and-death failures: getting called for last-second missions with almost no time to plan, making amends for an airstrike that killed family members in the tribe we had just partnered with, having key Marines wounded just before starting a major operation, having Marines killed. Lima Company developed a reputation for being able to adapt to anything that the insurgents—or our own chain of command—could throw at us. With that kind of background, you’d think (because I sure as hell thought so) that I could roll with the punches around here pretty easily, but the second year of farming has been harder than I anticipated. I already had most of my cover crop/pasture established. I knew where I wanted to plant corn. I knew my pasture rotation for the pigs. I grew up around farming. I know that weather alone can make and break a plan. I’ve written “farming in partnership with Nature” more than once on this website, but Nature keeps outmaneuvering me. The pigs are already on high ground, but when we’re twenty-five percent above our rainfall average for the year and another 1.87” falls in three hours, the pigs turn every paddock into a mud hole. I’ve tried spreading out the damage by moving them daily, but the physical effort and losing several days of planned pasture in less than a day takes a toll. Sometimes I keep them in place, deciding to offer up the decimated paddock as a “sacrifice area”. I reseed sacrifice areas. There’s a seed and labor cost, but the soil needs cover with diverse plant life to to make pasture next year and to support the soil food web below ground. I’ve already reseeded a few sacrifice areas. It’s not just the pastures. My cornfield rows are as thin as the lines at the Dane County Fair yesterday afternoon when it started to rain. I had a checklist of planter problems confined to two acres -slipping planter transmission, broken shaft keys for each row, seed too deep, seed to shallow, mis-sized kernels that a plate planter turned into cornmeal (and yes I did test the planter -it worked beautifully when I tested it). It’s not efficient to raise your own feed at small scale, but I plant a couple acres of open-pollinated corn for a few reasons: the corn has higher nutritional value than modern hybrid corn, it gives me some control over the feed and feed quality my pigs get, and being able to save and replant corn seed gives me some independence from the agricultural-industrial food complex. Without much of a corn stand, I decided to focus on next year —making sure it would become a good pasture. I wanted to till between the rows first to knock back some weeds (cultivating with a tiller -tilltivating) and then broadcast seed with the truck. (Check out the Facebook page for Videos -July 11th) But if I tilled first —which takes a few hours—and then it rained before I could seed, the truck would have been a disaster in the field. The corn was already pushing the height limits of what the truck can drive over without snapping stalks. (Because rains had already kept me out of the field.) So I broadcast 20 lbs of pasture mix first and tilled it in as shallow as I could, which was already putting the seeds a little too deep. The predicted light rain came in a pounding 3/4” —burying the seeds. Knowing that wasn’t going to lead to a good pasture stand, I went out the next morning and hand-broadcast another 10 pounds of pasture mix per acre to compensate. The good news is that plenty of little grass and clover seedlings have popped up between the corn rows. There is hope. Maybe it’s the primacy-recency effect, but this seems harder than combat. There’s no snapshot decisions under fire and the adrenaline rush of a new split-second plan to still accomplish the mission. There’s no going home if I make it through a 7-month deployment. Mistakes unfold over the season, the compounding results hanging with me into the next. I also realize that the strength and resilience I had in Iraq was really the the strength and resilience of Lima Company behind me, “the Force” if you will, of brotherhood forged under fire. It’s very different to work alone. If you’ve had a shitty week or month or year and reading this helps you step back and put your failures in perspective with your purpose, then I’m glad. But I didn’t write this with any particular audience in mind. I needed to write this down for me. In the long view, I’m still doing some good things here, despite all the setbacks. I’m producing high-quality, healthy, happy animals. My pastures are as good as I’ve seen on other pastured pork farms. All the feed I use now is organic or transitional organic (I won’t purchase any Non-GMO feed after last year. Non-GMO still uses pesticides that harm native pollinators, herbicides that kill soil life, and synthetic fertilizers that choke our waterways with algae bloom). I’m building soil. I’m building soil life. I’m healing the land. I’m raising food that feeds my family and a small circle of friends, old and new. I’m gonna roll with this. If you want to really comparison shop, go see how various farmers raise the food you buy. Farm visits -if they are truly open to your questions- let you see behind the curtain. Every time I visit another farm, I learn something. Sometimes it's a pleasant surprise—sometimes it’s a disappointment.

There's no scripted farm tour here. It’s a chance for you to get a snapshot of what we do well—raising happy, well-fed pigs—and our challenges—my Boxelder and thistle problem in the front pasture because I don’t use herbicides. Email, call, or text me to set up a visit so I'm not mowing back fence lines where I won’t hear or see you. Kids welcome. So come and stick your snout in our business and see how we make delicious pork. |

Ryan Erisman

Former Marine Infantry Officer. Iraq Vet. Interested in Regenerative Agriculture at any scale. Archives

February 2023

Categories |

Odyssey Farm, LLC.

The Odyssey Farm Journal

Odyssey Farm, LLC

|

Dane County Climate Champion

|

608.616.9786

|

Copyright © 2016

RSS Feed

RSS Feed